On July 16, 1945, the cruiser Indianapolis sailed from Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, carrying one 15-foot crate. Inside were the components for the first atomic bomb destined to be dropped on a city.

It was being shipped to Tinian Island in the western Pacific, and its final destination a few weeks later would be Hiroshima. It left San Francisco just four hours after the first successful atomic bomb test in history, in the New Mexico desert.

Sixty years is a long time to keep even such an immense memory alive, but several books published recently bring these events into sharper focus than ever before. Several are biographies of key figures like Robert Oppenheimer and Edward Teller, but one is billed as a biography of the bomb itself. "The Bomb: A Life" by Gerard DeGroot (Harvard University Press), professor of modern history at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, benefits from newly available records, especially concerning the Soviet nuclear program. But mostly it is a skillfully condensed narrative of the nuclear era, fascinating in the selection of details and riveting in its revelations of how possessing nuclear weapons changed those involved, and changed America.

On the day of that first test in July 1945, no one knew what would happen. About half the scientists didn't think the device would explode at all. Enrico Fermi was taking bets that it would burn off the Earth's atmosphere. It did explode, with such brightness that a woman blind from birth traveling in a car some distance away saw it. "A colony on Mars, had such a thing existed, could have seen the flash," DeGroot writes. "All living things within a mile were killed, including all insects."

America was now in sole possession of the most powerful weapon in history. The first effect of the bomb was in Potsdam, Germany, where President Harry Truman was conferring with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin, premier of the Soviet Union, then an ally in the war against Japan. After Truman received the news of the successful test, he was "a changed man" and "generally bossed the whole meeting," according to Churchill.

But there were other considerations, mostly to do with demonstrating American power, especially to the Soviet Union. Using the bomb quickly became a test of patriotism. "For most Manhattan Project scientists the bomb was a deterrent, not a weapon," DeGroot writes.

|

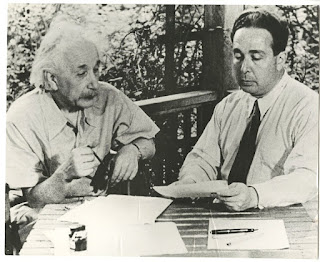

| Szilard and Einstein |

The petition was ignored, and Gen. Leslie Groves, the senior military official in charge of the project, began making a case that Szilard was a security risk. It's a pattern that would be repeated often.

|

| General Groves and Manhattan Project scientists look at what was left after the first atomic test in July 1945 |

Hiroshima was selected as the primary target because it had no allied POW camps. However, there were nearly 5,000 American children in the city -- "mainly children sent to Japan after their parents, U.S. citizens of Japanese origin, had been interred." It seems likely some of those children were from San Francisco.

The nuclear era began with the secrecy of the Manhattan Project, which is perhaps partly why it was accompanied throughout its history by lies and denial. They began with Hiroshima. As many as 75,000 people died in the first blast and fire. But in five years the death toll would reach 200,000 because of what the U.S. government denied existed: lethal radiation.

Even after the hydrogen bomb was developed in the 1950s (so powerful that the first test vaporized an island and created a mile wide crater 175 feet deep), the untruths continued. In 1954, Dr. David Bradley reported on 406 Pacific islanders exposed to H-bomb fallout: nine children were born retarded, 10 more with other abnormalities, and three were stillborn, including one reported to be "not recognizable as human." Such information was denied or routinely suppressed through all the years of testing, even on U.S. soil. Groves even told Congress that death from radiation was "very pleasant."

Even after the war, criticizing the bomb in any way became a threat to national security, an act of disloyalty that only helped the communist enemy. And so people were silent and compliant, and streamed into air-conditioned theatres to see movies about monsters created by atomic radiation.

This extreme weapon prompted extreme and contrary emotions, often within the same people. Some of the same Los Alamos scientists who cheered madly at the first news of Hiroshima were later shell-shocked with regret. Gen. Omar Bradley called his contemporaries "nuclear giants and ethical infants." Yet he pushed for developing the hydrogen bomb.

This peculiar combination of denial plus the immense power of thousands of bombs contributed to an era of deadly absurdities: the age of Dr. Strangelove. Yet reality was not so different, right down to the preposterously appropriate names: the head of the Strategic Air Command, Gen. Tommy Power, gave his philosophy of nuclear war in 1960: "At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win!"

The warp in American political life created by the bomb might be summarized in two statements. "In order to make the country bear the burden," said President Dwight Eisenhower's secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, referring to the Cold War arms race, "we have to create an emotional atmosphere akin to a wartime psychology. We must create the idea of a threat from without."

The second is more famous, but perhaps its connection to the bomb and its effect on America has been forgotten: Eisenhower's farewell address. "We have been compelled to create a permanent arms industry of vast proportions," he said. "We must not fail to comprehend its vast implications. ... We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."