In July 2025, beginning playwrights assembled at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut for the 60th straight year (though in Covid Pandemic summer, they gathered via Zoom.) The O'Neill's first formal program, the National Playwrights Conference, began in 1966 and never missed a year, though at times it was close. It is in most ways the oldest and most prominent and probably the most consequential play development program in the United States.An article in the New York Times described the 2025 conference, which hosted three playwrights for what seems like a week or two. But in July 1991 I had a wonderful two weeks at the one month conference, when there were twelve playwrights, plus directors, dramaturgs and lots of New York theatre actors of all ages. In retrospect it can be seen as close to the end of the conference's golden age, when founder George White was still running things, Lloyd Richards had been the Artistic Director since 1968 and was clearly the keeper of the spirit of the place, and August Wilson was the affirming presence--if he wasn't there with his own new play, he was helping develop the plays of others.

I was there to write a feature article for Smithsonian Magazine. I was not happy with their edit for publication--I offered my corrections but they ignored me, and so there were embarrassing errors, especially in the title and photo captions (such as referring to the playwrights as "students") in the article published the following March. As edited, the piece seemed to me to miss what I felt was essential to describing the experience: though individual playwrights worked intently on their own scripts, the entire process was communal. It was a living breathing community of well over a hundred (counting staff), to which everyone there was committed. Though a play (like the one I focused on) might be developed and produced in the first two weeks, the playwright would stay for the whole month, and be part of the process for others.

So what follows is a different version, assembled from my final draft with more quotes added from interviews and reporting, as much an historical record now as a magazine piece. More than thirty years later now, I've made a few new edits for clarity.

Even as an outside reporter, I was accepted into the O'Neill community and process for those two weeks. I spent some time researching O'Neill Center and playwrights conference history in their library and archives, and I sat at Eugene O'Neill's desk in the Monte Cristo Cottage in New London, but most of the time I was on the O'Neill Center campus. I was even absorbed into its social life, from the volleyball games to long conversations in the dining hall and on the "seaporch," and some beery hours at the onsite Blue Gene's cafe. I talked several times with all the playwrights, and just about everyone else, returning to my blessedly air-conditioned motel room in Waterford only to sleep.

I had a long and fascinating interview with George White, and several with Lloyd Richards, but my first interview was at a picnic table with August Wilson. I spent a fair amount of time with him afterwards, including listening spellbound as he enthralled the dinner table with dialogue he was hearing from characters in his next play. We had a few other adventures that weren't appropriate for the article, including my afternoon with the August Wilson gang.

August Wilson and I, and two others left the O'Neill grounds in a station wagon to perform various errands in Waterford and New London. These were the days of bank cards but not yet debit cards--you had to get cash from bank machines. But some cards only worked in machines of specific banks, so our quest for the cash we needed involved a search. After finding several machines that didn't work for some of us, we wound up at a small drive-in bank near closing time.

There was no machine outside, but some banks had them inside so August and I rushed in, looking frantically around. I think we had the same thought at the same time: we looked like bank robbers. August quickly tried to explain to a clerk, a woman in her 60s or so, who just smiled and called him "Mr. Wilson." Everybody at the O'Neill was required to wear a name tag all the time, and August had forgotten he was still wearing his. I thought it was all very funny but when we talked about it later, he said at the time he was really alarmed. He saw it as potentially a more dangerous situation, because he was experiencing it as a black man.

Though the Smithsonian Magazine (and others) referred to the National Playwrights Conference as a "tryout," it was at its core a development process. (I noticed in a later interview, August Wilson himself was quick to make that distinction.) Now that there are many, many "workshops" for new plays almost everywhere--and they've become so prominent that few plays get performed anywhere without going through one or more--I recall a couple of points I didn't stress for a general audience. One was Lloyd Richards' emphasis that the O'Neill protected the playwrights from potential deal-makers during the Conference, but never takes a portion of the playwright's income on any subsequent productions. "We don't mortgage the playwright's future. This place is unique." (Though I'm not sure if that policy is maintained today.)

The other point was made by a couple of the playwrights as well as Richards: that the O'Neill takes care not to overwhelm the playwrights and makes sure they make the decisions about their own plays. A few of the more experienced playwrights in 1991 had observed or been through processes elsewhere in which there were "too many cooks." In later years, especially in the decade when I was seeing a lot of contemporary plays, the over-workshopped play without focus and with less life than it potentially could have, became a typical experience.

The Times piece about the 2025 conference stressed the precarious finances that limited the number of playwrights to three. As this piece notes, there were anxieties about the survival of the program even in 1991. There were twelve playwrights instead of 14 or 15, and aspects of its usual procedures were curtailed that summer due to financial considerations. After Lloyd Richards retired from the O'Neill in 1999, there were more changes, including some controversial ones (I noted some in this 2006 post. I note other changes in this 2014 book review.) The O'Neill has been successful in increasing the participation of women and writers of color, and there appear to be some physical enhancements to its buildings. But I'm not sure how much of this 1991 process survives. So this piece becomes historical perhaps in more ways than one.

|

| August Wilson and conference artistic director Lloyd Richards at the O'Neill |

In 1979, an unknown playwright received a brochure from a friend that described the National Playwrights Conference, a month-long summer residency at the Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut. Scrawled on the brochure was the friend's instruction: "Do this!"

So he sent in a stage play and a play for television (the two conference categories) before the annual December 1 deadline, along with his stamped self-addressed envelop. There were at least a thousand others trying to be one of perhaps fifteen playwrights selected to work on their plays with the help of some of the best actors, directors and other professionals in American theater. The envelope came back with bad news.

He sent another two scripts the next year. This time he got a form letter from Lloyd Richards, the conference Artistic Director, encouraging him to keep writing. So he wrote the best play he could and sent it the next year. When his self-addressed envelope came back again, he threw it across the room.

Later, when he thought to open it, he discovered that he was a finalist. Soon he got the telegram inviting him to spend July on a rambling farm caressed by the smell of the sea. "Nothing I've experienced in the theater quite matches the excitement of that," he said. "I guess what it said was, 'yes, you can be a playwright.'" That first play he took to the O'Neill was

Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, which made it to Broadway and was highly acclaimed. It changed his life, and American theater

The 1982 conference was such an inspiring experience for him that he immediately set out to repeat it. "The first thing I wanted to do was come back," he said. "I didn't have an idea for a play, but when I got home I said to myself I have to write a play by December first. I just have to write a play because I want to go back up there. And I did."

That play, which he worked on the next summer at the O'Neill, was eventually titled

Fences. It won August Wilson the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. In subsequent years, August Wilson returned to the O'Neill to work on

Joe Turner's Come and Gone and

The Piano Lesson, which won the 1990 Pulitzer.

This is one of the more recent playwright conference legends but hardly the only one: O'Neill Center plays and playwrights have energized international theater for more than a quarter century, winning several more Pulitzers as well as Oscars, Emmys, Tonys, Obies, and even a Nobel Prize for Literature.

Among the other prominent American playwrights the O'Neill has nourished are John Guare, Wendy Wasserstein, David Henry Hwang, Christopher Durang, Lanford Wilson, Charles Fuller, Lee Blessing, John Patrick Shanley and Beth Henley. Michael Douglas, Meryl Streep, Charles Dutton, Al Pacino, Jessica Tandy, Cynthia Nixon, Kevin Kline and Raul Julia are some of the actors who have participated in this protean enterprise.

Although many theater institutions now develop and showcase new plays (notably the Actors Theatre of Louisville), the O'Neill pioneered the practice, and in many ways it remains unique. For playwrights it is a trial by Paradise in a four week Eden, a working idyll demanding both openness and nerve, where they are privileged and condemned to creating in a state of grace under pressure. For all participants it is a necessary oasis, a temporary Utopia, where they can live out ideals of sincere community with hearts and talent joined, and commit to the real work of making theatre, protected from the pollution of other agendas.

How all this actually works is the O'Neill Center's mystique. Its history and prominence, its physical environment, its process, and something that might be called its ethic, are the elements that make it an indispensable asset to American theatre.

That's also what makes playwrights determined to come here, along with such legends as August Wilson's. "Coming to the O'Neill is something playwrights want to do," said P.J. Barry, one of the 1991 writers. "It's part of the experience of being an American playwright."

As a boy growing up in Waterford, George C. White had played in the barn on the Hammond estate, a 95 acre spread overlooking Long Island Sound. When White was a young story editor of the classic George C. Scott television series,

East Side, West Side in the early 1960s, he learned that the estate's then abandoned buildings were about to be destroyed. At least one was scheduled to be burned as practice for the Waterford fire department.

He hit upon the idea of saving the estate by dedicating it to the theater and naming it after Eugene O'Neill, arguably American's first great playwright, who spent his boyhood in nearby New London, and had lived out his last years in a house a few miles away. (Called the Monte Cristo cottage, it is now owned by the O'Neill Center and open to the public.) O"Neill set one of his plays on the Hammond Estate itself, despite Edward Hammond's habit of chasing young Eugene away from the grounds with a shotgun.

With $1200 in cash raised from a life insurance policy and the housing provided by Waterford friends, White convened the first conference on the estate in 1965. Attending were eminent theater professionals and twenty-one young playwrights associated with the embryonic Off-Off Broadway movement, who were drawn in part by the presence of Edward Albee, then the only new voice in a generation to break Broadway's stranglehold on American theatre.

It was a tumultuous five days. "A lot of angry playwrights who wanted to be heard, who wanted in," recalls one of those young playwrights, Frank Gagliano, who drove a car up from Manhattan with unknowns Lanford Wilson and Sam Shepard as passengers. "The energy was extraordinary."

Decorous discussions under the trees among gentlemen and ladies in suits turned into shouting matches. The nineteen year old Shepard made an impassioned speech and stormed out of the conference, never to return. But some others (who included John Guare and Israel Horovitz) began talking about what they could do there, and giving new plays a start was the consensus.

|

| George White smiles, Edward Albee listens in 1965 |

The conference ended with the kind of connective---and predictive---symbolism that has become part of the O'Neill Center mystique: an act of "Moon for the Misbegotten" was performed in the old barn, directed by Jose Quintero, the champion of the then ongoing revival of Eugene O'Neill's plays. It would be only a few years later that his direction of this play would electrify New York.

The 1966 conference began with historical context: a performance of

The Contrast, a two act comedy by Royall Tyler written in 1787--it was the first American play by an American author. In the cast was Danny De Vito.

That summer and the next made the O'Neill Center's reputation, and almost ended its existence. So many of those angry playwrights who returned had subsequent successes in New York that an article in the New York Times dubbed the O'Neill "Tryout Town USA." But the elaborate productions were exhausting participants and fostering rivalries. In 1968, George White convened another meeting. "It became obvious that the first task was to abolish the artistic anarchy that had set in," White recalls. "We needed a strong artistic director."

White turned to Lloyd Richards, the director of Lorraine Hansberry's 1959 Broadway hit, "A Raisin in the Sun." Although Richards had directed one of those elaborate productions at the O'Neill (complete with exploding bombs and rifle fire), he immediately stripped the conference down to essentials, "to focus on its original intent," as Richards says today, "which is to serve the playwright and serve the theatre by developing these playwrights." White and Richards have guided the O'Neill in that direction ever since.

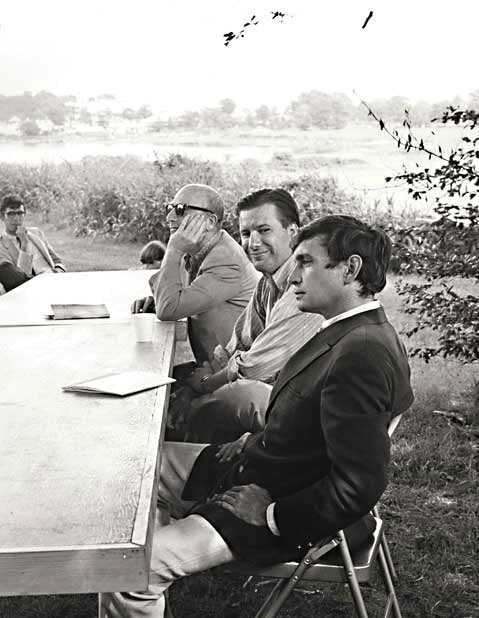

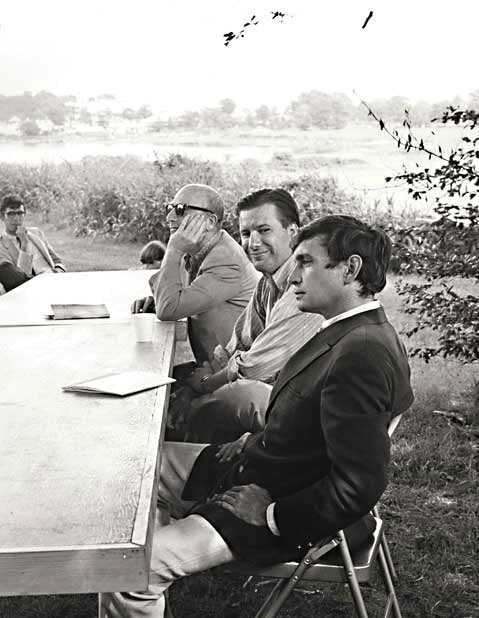

|

| Playwright Tom Szentgyorgi and August Wilson in 1991. Smithsonian Magazine photo. |

Every day is a week...This is the repeated refrain, the conference mantra. Everyone uses it to describe not only the intense four-day rehearsal period for each play, but the O'Neill experience itself. Take for example the progress of "Dinosaur Dreams."

On a golden Monday morning, the first day of July, Tom Szentgyorgi rode in the blue O'Neill van down a curving two lane road through lush trees to the blue sign announcing the O'Neill Center in gold letters. Along with his fellow 1991 playwrights, a couple of whom were with him in the van, he would split his time for the next month between a room in a borrowed dormitory a few miles away where the living conditions were somewhere between collegiate and penal (one dorm has been known for years as "the Slammer"), and this quaint collection of frame buildings floating on 8.5 isolated acres, redolent of history and hopes, scattered with immanence. They'd left Manhattan's noisy insistence just a few hours earlier. Here they hear little but the calm commentary of birds.

There's time this first morning for a fast tour of the grounds. The indoor performance space is housed in the red barn, now refurbished, air-conditioned and named after two early O'Neill Center supporters, Rufus Rose (a pioneer puppeteer who created Howdy Doody, and was a mentor to the Muppet's Jim Henson) and his wife Margo. Next to the barn is the outdoor amphitheater, a shadeless suggestion of ancient Greece, though the ship's mast serving as a lighting tower gives it a nautical New England touch. A new wooden platform is under construction there, replacing the first one that Michael Douglas once augmented his actor's salary helping to build.

Some of their plays will also be performed at the Instant Theater, a small platform surrounded by bleachers nestled next to the signature copper beech tree. It was here that Lee Blessing's "A Walk in the Woods," the later celebrated play concerning conversations under the trees between a Soviet and an American arms negotiator was first performed, on July 4, 1984.

As soon as all the playwrights arrive, the work begins. Dressed in polo shirts, shorts and sandals; jeans, t-shirts and sneakers, they gather in a mostly bare room at one end of the Production Cottage, a long frame building of offices that inside as well as out suggests an elongated train caboose. In folding chairs or sprawled on the floor, they listen to each other read their plays. The first play they hear is "Dinosaur Dreams" by Tom Szentgyorgi.

Tom, whose last name (according to his program bio) is pronounced "szentgyorgi," but who tells everyone to say it as "St. Georgie," has been an assistant director and literary manager, and after the conference will become the associate artistic director of the Denver Center Theater Company. He'd written a few short theatre pieces, but "Dinosaur Dreams", is his first full length play. Focusing on a young couple, it has a contemporary urban setting and theme, and a mood that mixes comedy and drama.

|

| The 1991 playwrights. Smithsonian Mag. photo |

Many of his fellow playwrights in 1991 had also logged years in theatre, but half of them were here to work in a new form. Phil Bosakowski, Patricia Cobey and Peter Selgin had teleplays, while Gannon Kenney, Matthew Witten, Rick Cleveland, Jeffrey Hatcher, Paul Zimmerman, Charles Schulman, John Darago and P.J. Barry had stage plays. In age and experience the group ranged from Kenney, a Harvard graduate student, to Barry, a seasoned New York playwright and actor. Only two had been to the O'Neill before.

They would read to each other for the next three days. Besides gently starting the process of exposing a written script to scrutiny and transforming it into live theatre, this marathon introduces the playwrights to each other through their work, before they go their separate ways with their separate plays. They will need each other's support and understanding for the compressed rigors ahead, so the bonding this common experience creates is considered so important that this is one of the few events the O'Neill bars to outsiders.

But as he reads his own play, such purposes are lost on Tom. He is conscious only of the strange sound of his characters' words coming out of his mouth, and the salt deposits of sweat forming on his shirt.

At the sound of an old-fashioned school bell, the playwrights adjourn to cafeteria-style meals at the 19th century frame house known as the Mansion. They carry their trays into the added-on dining hall or through a warren of offices out to what is called the seaporch, with the Center's most dramatic view. From its red picnic tables under yellow and white striped awnings, they can gaze down the sloping meadow bordered on one side by woods, to the sand dunes and swirls of green and yellow marsh grass, and past the white beach to the steady blue of the Sound. Breakfast here is sometimes accompanied by rolling billows of fog, and at night this silent hill is the best vantage for viewing a sky crazed with stars: the kind you don't see in Manhattan.

Tom's first dinner is a working one. He confers with his dramaturg, August Wilson. Dramaturgs didn't exist in America before the O'Neill Center was searching for a way to get critics involved in the process, and borrowed the term from Brecht. Today in the many theatres that have them, their function is usually production-oriented. But the duty of O'Neill dramaturges is to assist the playwright in remaking the play. So in addition to critics like the New Yorker's Edith Oliver, O'Neill's dramaturges now include other playwrights: in 1991, Corrine Jacker and August Wilson.

"Initially, I was pretty nervous," Tom said of his first private meeting with August. "But right away we were talking the right language. Mostly we looked at places in the script where I can relate some of the peripheral action more strongly to the main story---a kind of rhyming."

August talked to Tom about the theme of his play as expressed in his synopsis---personal consequences of economic retrenchment in the 1990s (or as director Bill Partlan later described it, "adapting to a world that's gotten colder")---and questioned how this theme is carried out. "I think I can be helpful," he concludes. "There are mistakes that everyone makes. Having made those mistakes, I can point them out... You can stay up all night long and read your play over and over again and you won't see these things until someone points them out to you."

For the next few days Tom works on rewrites, first on his old Olivetti portable, but he soon finds he has to book time on the center's only computer, because he has to write faster. He has already talked to Lloyd Richards about the play (Richards is famous among playwrights for his concise analysis) and his director, William Partlan (who coincidentally was August Wilson's first O'Neill director.) "I've got to make my play more than a bag of scenes," Tom says at lunch on Tuesday. "How well does each scene advance the plot? Does it elucidate what the play is about? I'm going through and following the arc of each character, and rewriting that way. I have to think those things consciously, but at the same time I can't over-determine the play and kill it with theory. My task is to fire up my imagination and put it in the direction I want to go. To me that's the hard part."

After missing a few meals, Tom reappears in cutoffs and a sweater on a cool, rainy Wednesday afternoon to confer with August again. Together they spread old and new pages on a round table in the dining hall, and scissor and tape the script together. In particular Tom has rewritten one major scene. Still, there are two other scenes they agree still have problems.

But at week's end the first test of both solutions and problems is about to come, when the process moves from the page to the stage.

|

| Years later, the amphitheater where the Swedish company performed in 1991. |

The first weekend is unusual. The playwrights' marathon reading normally occurs here during a pre-conference in May, but last-minute government funding cuts meant that those three days had to be made up within the conference itself in July. Besides shortening the rewriting time (resulting in what playwright and O'Neill veteran Jeff Hatcher called "paroxysms of typing") this meant that there would be no performances ready for the first weekend. This gap was filled by the visiting Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden company, with a new play by Swedish author Lars Noren about Eugene O'Neill's last days at the Monte Cristo cottage.

After two public readings of a new English translation, the company did one act in Swedish just for the O'Neill community with Max von Sydow in a dazzling tour de force as the playwright. The company's presence was another loop in the spirals of O'Neill history, not only for the Swedes, who were seeing the very landscape O'Neill wrote about (including a fortuitous fog) but for the conference, since owing to American indifference, several of Eugene O'Neill's last plays were first performed in Sweden.

This international input is also a conference tradition, dating back to 1969, when poet Derek Walcott brought his theatre company from Trinidad, and 1970, when West African writer Wole Soyinka came to work on "Madmen and Specialists," a play he had begun writing with ink he made from coffee grounds while a political prisoner in Nigeria. (George White got him into the country by inventing a sponsoring organization and faking its letterhead.) Soyinka won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature.

On Sunday, the quintessential fog swirls up into the big beech tree and forms wispy walls around the members of the 1991 Playwright Conference community assembled on the bleachers of the outdoor Instant Theatre to hear Lloyd Richards give his traditional welcoming speech. Until now, there were only the playwrights, directors, dramaturges and designers, and the O'Neill technical and administrative staff. But the crowd includes actors now, ready to begin in earnest the O'Neill process, with its high theatrical mood of anxiety, nobility and sweat.

|

| The theater barn in 2025. New York Times photo. |

Monday, July 7 is the first hot and humid day of the conference. (There would be many more.) Tom walks out of the midsummer sunlight and into the dark cavernous barn for his first day of rehearsal. He and the others involved in "Dinosaur Dreams" will have only four days to do what normally takes a month (

Every day is a week, every week is a...) The names of his cast were posted on the Production Cottage bulletin board on Sunday, so Tom had only a short time to cope with the notion that he will be working with stage veterans Anne Pitoniak, Victor Raider-Wexler and Phyllis Somerville, as well as seasoned young actors Jane Adams, Joe Urla, Robert Knepper and Tony nominee J. Smith Cameron.

Tom sits in the shadows at one end of the last row of folding chairs, silently listening to the first read-through by the actors arrayed on the still blank stage. He scribbles on his script, and occasionally gets up and paces behind the raised platform of seats. At the other end of the row is August Wilson, dressed in the same khaki safari outfit he bought for his first conference in 1982, writing notes on a yellow pad. Bill Partlan watches from closer range in the front row, nodding his encouragement.

After lunch, the actors reassemble on the stage and ask questions about their characters. The action of "Dinosaur Dreams" concerns a young couple, Bob and Paula, deciding on marriage in a time of personal and societal uncertainty. Actor Joe Urla, who plays Bob, begins asking about his character in the play's first scene, set in a bar where Bob tells his friend Mark about Paula.

"Bob describes meeting Paula in very idyllic terms," Urla says. "Is that what really happened?"

"No, he's idealizing her," Tom replies. "He's bragging to his friend. But he's being sincere about his feelings for her."

Others talk about Bob's actions and reactions as the play progresses and as Paula drifts away from him. Does he understand what is happening around him?

"Bob is socially shallow," Tom says. "He's not aware of the world. But he's not emotionally shallow---he's ready to deal with relationships. That's why he fixates on Paula, and on marrying her as the solution."

The character of Bob's friend Mark, who works on Wall Street, is easier to summarize. "He's a shark," Bill Partlan suggests. But then the question becomes what kind of a shark: street-hardened or sophisticated? Throughout the rehearsals, actor Robert Knepper will experiment with Mark's accents and attitudes.

"How does she know these colors?" August Wilson asks, as Paul begins a scene reciting a list of arcane shades, to humorously illustrate all the choices for a wedding dress besides white. "Is she an artist?"

"She's a teacher," Tom says. "They're colors in a big crayon box."

"I've taught nursery school," says actor Jane Adams, who is playing Paula between her Broadway appearances in "I Hate Hamlet", and a role in a movie directed by Barbet Schroeder. "These are the colors we remember from our crayon boxes, but they aren't the colors kids have now."

It is the actor's role in the process to see the play from the point of view of the character he or she is playing. They contribute by questioning motivations, the logic of actions, the journey of the character from beginning to end, the character's place in advancing the dramatic action, or even how the character talks. When one actor in the O'Neill production of "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom" told him his line didn't sound like a white Chicago cop, Wilson asked him what the cop would say. "He said, you know, things like, 'look, buddy, if you want it in a nutshell,'" August Wilson recalled. "That line's in the play to this day."

|

| Actors Jane Adams and Joe Urla work on Tom's play in 1991. Smith. photo |

"The actors who come here are so willing to give," Wilson said. "They come up here without knowing what play they'll be working on---they don't come because they get to act in this cool play, they come for the conference. I know they helped me."

"To me, this is sanctuary," said John Seitz, an established stage and film actor who has been coming to the O'Neill for 19 years. "I'm not an actor up here---I'm a resource who acts. You work with a playwright in a more direct way than you're allowed to in the real world. It's like renewing your vows, reminding yourself why you became an actor." It's the same reason he does workshops and readings in New York without pay, he added. The money comes from television. "But what do I play? Cops."

The actors read through the play again, and Tom paces behind the seats, listening to the dialogue as it competes with the ringing phone in the box office, stopping to scratch out lines that the actors' gestures and intonations make unnecessary. He pays particular attention to the scene in which Paula introduces Bob to her parents, his major rewrite so far. He's inserted a new event: Paula's father has lost his job, and her mother is upset about it. This carries forward his theme while adding extra drama to the scene. The actors don't know this is a revision, but from now on new pages are color-coded.

As the actors leave, Tom huddles briefly with his director and dramaturg. They agree the new scene works, but the two other scenes that troubled them don't play well. At dinner, Tom ponders the day's lessons. "I have to sort out the questions that pertain to acting---questions that actors would act even if they were doing Shakespeare---from the questions that pertain to problems in the script. I've got a lot of work to do in the next three days. I'm getting tired just thinking about it." After dinner he returns to the dorm to work on changes, a jar of instant coffee stuffed in his backpack.

Tuesday turns out to be Tom's worst day. Bill Partlan begins instructing the actors on when and where to move on the stage, the process known as blocking. The actors are carrying their scripts, but like the minimal set and props now beginning to appear, this will not change for performances. Long gone are the elaborate sets and competitive acting of the first two years. "Productions are restricted to only what's essential to express the material," is the Lloyd Richards' rule, so there are only simple, modular units that stand in for the requisite sofas and park benches; only essential props, no special lighting and no costumes except for clothes the actors supply for themselves. (A designer also draws a rendering of an ideal set after meeting with the playwright. It's posted for the audience to see, but its basic function is to give the playwright a sense of design needs and possibilities.)

Similarly, actors don't memorize their lines but carry their scripts as they play their roles. Along with the easily altered sets, this allows the playwright to keep making changes up to the moment of performance (which August Wilson for one admits that he's done.) With only four days of rehearsal, Richards points out, the script-in-hand method ensures that "playwrights will hear the lines they wrote, not an approximation."

Today the playwright hears the lines he wrote last night, and doesn't like them. No one else does either, so a frantic night's work is negated. This only makes a long day longer. Tom escapes momentarily from this repeating concentration in the dark, to the sunlight and salt air outside. "O the excitement, the glamour of live theatre!" he proclaims to the oblivious gulls.

But on Wednesday his mood lifts. His stage manager plays the recorded song she's using as background for the first scene: Peter Gabriel's "Sledgehammer." Tom brightens. I haven't heard music in so long!" Today's work on the latter part of the play helps to focus his thoughts on what he needs to change in Paula's earlier monologue, a pivotal moment. He is relieved that this is his last major rewrite.

Thursday morning they work on a new scene. Instead of talking directly to the audience about her hitch-hiking flight from Bob, Paula now re-enacts it in cinematic swatches. The director, stage manager and lighting designer discuss the required sound and light changes. Ahead are compressed versions of dress and technical rehearsals. Friday night, "Dinosaur Dreams" will face its first audience.

Meanwhile the special life of the O'Neill Center has gone on. An ad hoc company of actors has rehearsed and read all three teleplays to the community audience. One of the writers, Peter Selgin, had already become a conference legend for feverishly rewriting his teleplay almost completely, much of it on a broken typewriter, in what seemed like one continuous stint, punctuated by frequent showers. During the Swedish play he was seen in Blue Genes, the on-site café, writing alone at a table amidst the intermission revelers, dressed entirely in black. He reminded August Wilson of the playwright of a past summer who stayed up for four successive nights rewriting his play, only to sleep through its first performance.

By the end of the second week, there are 130 or so people on the premises, including visitors, all wearing the requisite name tags, some of who are scouting new plays for their New York and regional theatres. But no business is permitted on the grounds, and to protect the playwright in a vulnerable time, the O'Neill keeps performance rights to every play for the length of the conference plus six weeks, after which (unlike many other development programs) the O'Neill takes no money from any subsequent production.

By this time there is the usual catalogue of summer camp injuries, including a few more exotic accidents, like the playwright who got a moth in his ear, and the television executive who was sprayed by a skunk.

And then there was the Soviet playwright who arrived unexpectedly, and was found wandering through Kennedy airport by a nun. All will become part of O'Neill Center lore.

At night there are group trips to local movies, and visits to the nearby tiny amusement park down on the beach which sometimes supplies unwanted polka music to outdoor performances. In Blue Genes, a playwright plays piano while a staff member sings show tunes, and director Clinton Turner Davis takes on all comers in Scrabble, while conversation continues on the patio into the night.

There is talk everywhere, invigorating and intoxicating: Evocations of theatre history by people who were there, by participants like teleplay director Jay Broad and story editor Max Wilk, and guests like Ben Shaktman (founder of the Pittsburgh Public Theatre), who recalled encounters with Carlotta O'Neill, the playwright's widow. The names of Odets, Miller, Williams and Albee are spoken, anecdotes told, legends continued in the oral myth of the American theatre.

August Wilson mesmerizes his dinner companions one evening with a description of his latest play, complete with dialogue. Patricia Cobey and Corrine Jacker trade first childhood memories of live theatre (Patricia's was sneaking off to matinees at New York's Theatre de Lys; Corrine's was watching Sylvia Sidney carry her curtain-call roses in Chicago.) As they lingered by the stone wall one evening, gazing at the ocean in the distance, their conversation underlined commitments to a life in the theatre that characterizes the O'Neill. "Whenever someone I know is having problems," Cobey said, "I tell them to take an acting class. It always straightens you out. That's where you learn that you can't lie."

|

| Martha Wade Steketee photo 2013 |

And there are periods of stillness and quiet. The black and white lawn chairs on wheels, the faded red picnic table sloping down the foot-browned grass, are etched as objects in the landscape as surely as the elegant and solitary tree in the center of the meadow, or the stand of furry green trees bordering the sand, the metallic blue sea and the jagged line of blue woods across the sound. There is a nourishment of stillness and place to match the nourishment of motion, the blood flow of talk, laughter, smiles, bodies touching each other in the medium of air, of sight, of sympathy. The flowers, the stone wall. The damp, the smell of the sea. The high motion of faint dark clouds against the higher solid banks of lighter gray. The sense that humans do belong here after all.

And then there is work. (

Every day is a week.) Concentration makes every moment larger. "There are no distractions, it's just the work. That's what I like about it," said Brian Siberell, an advisor to the teleplay process here, but whose New York days in charge of developing movies for HBO are broken by telephones and faxes. Distant from the outside world and completed concentrated on the task at hand (the condition, Patricia Cobey notes, of a child at play), there is an analogous focus on every person and on every moment, even in non-working time.

And at rehearsals, meals and every performance, there is Edith Oliver, who after twenty summers as a dramaturg is such a beloved embodiment of the O'Neill that her oil portrait hangs in the Mansion living room. "The mysterious thing is the feeling we all seem to have for the O'Neill," she says. "The question here isn't, 'May I join you?' You're always welcome. This is the O'Neill!"

On Thursday night Tom tries to relax. After dinner he joins in the traditional volleyball game near the Instant Theater. But these games, which had begun with informal irony and mock heroics when the players were playwrights and staff, had become more seriously athletic as more actors arrived. Tonight the dust rises in the bright dusk, and when the players quit early as the Instant Theater is prepared for a performance, Tom is not sorry.

|

| The Instant Theatre, renamed the Edith after beloved critic Edith Oliver. Steketee photo 2013. |

Everyone in the community attends every play, and so Tom puts aside concerns for his own to watch Gannon Kenney's "Weller," a short, two-character drama with Mason Adams (of "Lou Grant" and Smuckers' commercials fame) and Tom McGowan (fresh from his Tony-nominated role in La Bete.) It is a spectacular evening, the clouds packed in pink and reflecting purple in the sea. As the audience gathers in the deepening blue twilight, Gannon sits high in the corner of the top row of bleachers---"ready to jump" he shouts at someone. He has rewritten half his play, as Tom can see from the pink and yellow pages amongst the white in the scripts which the actors carry. But the play is well received, both comforting and daunting to the playwrights yet to be performed.

The gathering is repeated on Friday night, this time for "Dinosaur Dreams." Besides the Center community and visitors in theatre, there's a audience that comes from Waterford and New London. They're generally a savvy group, as George White describes them, knowledgeable and excited, expecting the script-in-hand acting and minimal O'Neill production but nonetheless interested in a good night of theatre. They are the play's first real audience-and, White suggests, they take their part in the process seriously. It's a public that has developed over the years, along with the O'Neill itself.

At the barn door most O'Neill people head to the balcony (formerly known as the hayloft), leaving the first floor folding chairs for paying customers. Tom escorts his visiting parents to seats in the back row center, but he will watch (or rather, listen) while pacing back and forth near the entrance.

Before the play, Lloyd Richards gives his ritual speech explaining the O'Neill process in its historical context, and what the audience should expect. "Without new playwrights," he says, "theatre is a museum. From the fifteen hundred plays submitted this year, we have chosen twelve---not because they are ready for Off Broadway, but because we spotted a unique voice."

This speech, he says later, is important primarily for the audience. "The audience must also be focused. They, too, have a role in the process...Things that we do that seem ritualistic are very important to becoming focused."

In conversation, Richards reiterates that the purpose of the selection process is not to find the best new plays but potentially the best new playwrights. An initial group of readers performs the first screening. Then Richards and a smaller group reads the ones that are left. He says that the ten percent rule usually operates, a percentage breakdown he claims is uniform throughout every creative screening process he's encountered. Ninety percent of what is submitted is not worth considering. The plays selected come out of the remaining ten percent. (The total number submitted doesn't seem to matter, he said. What is clearly worthy of consideration is generally always ten percent.)

Richards took time to explain the various checks and balances in the process, but playwrights still often find it daunting. When one famous playwright with O'Neill productions in his past was asked why he doesn't work on his new plays there as August Wilson does, he intimated that he is intimidated by the screening process. He is afraid that his play won't get past the first layer of readers, and he would feel crushed. (

Update: now it can be told. That playwright was Christopher Durang.)

Tonight Tom's play progresses without a hitch, although the actors are contending with the noise of the air conditioning for the first time. The audience laughs at some of the right places, and doesn't at others; they react with special favor to the kisses.

With Tom's new scenes the play now runs an hour and forty-five minutes, but there is no natural place for a break, so the audience as expected seems a little groggy at the end. Still it did not take long for the audience to forget that the stage is mostly bare and that the actors carry scripts. The alchemy of theatre works fast.

Afterwards Tom takes his parents and other family to Blue Jeans, where the program of his play is tacked up over the bar, honoring it along with the others performed so far. In a couple of days the community will gather again for a critique of his play, but over drinks in the paneled interior and out on the patio of Blue Genes, the talk has begun already, mixing discussion of dramatic points with resonances of personal experience. "I know what Bob was trying to do by marrying Paula---I tried it, and it doesn't work!" "I know that guy Mark-I've dated him!"

There is another performance the next afternoon. Playwrights have been known to make script changes at this point but Tom doesn't. There are two differences however: Robert Knepper's Mark seemed too aggressive Friday, so he plays him with a smoother slyness on Saturday. And at this performance Tom actually sits down to watch, at least part of the time. "I saw the wisdom of having two performances," he says afterwards. "I was totally at sea the first night. Going through it again I could actually listen to the audience."

The critique has its own rules and traditions. Only the play itself is to be discussed, not the performances or production. Summaries of these critiques are sent to the playwright, dramaturg and director, but sometimes not until months later.

For Tom the play development process is over, but the lessons of it aren't. "There are still problems," he concluded, "but I ended up with a much better play than I came here with."

"The performance is just one part of the process," Bill Partlan points out. "The playwrights might learn more from the actors' first reading." "The actors ask the playwright questions about their character," August Wilson said. "Long after the performance, when you're at home rewriting, you'll hear those questions in your head."

What Tom and other playwrights experience is a process unlike any other in the American theatre. All the usual theatrical roles are at least slightly different, as everyone and everything focuses on the playwright. "The role of the director in the commercial theatre is to make the play work," as Lloyd Richards explained. "Here the director tries to discover what doesn't work, and to work on that with the playwright."

The playwright is everyone's focus. "As a dramaturg, I'm an ombudsman for the playright, to see that what the playwright wants done, gets done," says Corrine Jacker, a two-time O'Neill playwright and seven-time dramaturg.

This emphasis is particularly telling in how teleplays are developed. "As a producer, I get what I want," said Philip Barry, a TV veteran serving as story editor (the equivalent of a dramaturg) at the O'Neill. "This is about what the author wants."

"In TV, writers lose control of their scripts very fast," says Jay Broad, who directed the teleplays. "Here the author listens to the director and story editors, but the author makes the decisions."

The actors also subsume themselves to the playwright's needs, to the extent underscored by the O'Neill tradition that at the end of the performance the actors do not take bows. Yet many actors, directors and dramaturges happily return to the O'Neill, year after year.

It all adds up to the O'Neill ethic and the O'Neill experience. "There is a wonderful feeling of good will," Patricia Cobey observed. "Down to the ground, solid, doing the work---no hype. That's kind of rare in theatre...The place feels authentic to me in that it says that it is committed to the exploration and development of plays in progress, and it turns out to be literally true."

Like Tom, Patricia had gone through the development process to final production and critique with her piece, "Eating Beige." "Now I'm in the second part of the experience-going to rehearsals of other plays, to performances and critiques, and talking to people. It's just as much a part of the process to me. Some writers feel a little bruised at this point, but Patricia didn't. Speaking of her director, dramaturg and actors she said, "we didn't have conflict but we had arguments, very good discussions. It was stimulating to have these different sensibilities concentrated on my work."

She described her response to her critique with a metaphor from painting. "When I'm painting in blue, I'm not interested in what people say who think I'm painting in green, or should be. But if they say something about the shades of blue I'm using, then I'm very interested."

Phil Bosokowski, whose credits include writing for the David Letterman show and Garrison Keillor's American Radio Company, was also taking a break after his teleplay production and critique of "How I Got My Apartment." He described his experience so far as "hard work, fast work, clear-headed comments from the audience. I knew coming in that this script had some weak links---I was close to the characters and the objective, but now I think this is a worthy project with a future life. Or if it doesn't, it makes a good 'calling card' script."

Gannon Kenney, as the youngest but not the least theatrically experienced of this year's playwrights, with one of the older and more experienced actors in Mason Adams, was fascinated by what the actors brought to the script. "I'd never had a production before. Just readings, and nothing like on this level. It was fascinating."

Gannon was surprised at how fast the writers bonded. "Literally, within hours. That shocked the heck out of me. People really pay attention to each other's work, not just their own."

As Tom, Patricia , Phil and Gannon reflect halfway through the 1991 conference, the work is still intense for those whose plays are still in progress. This Saturday afternoon, actors bathed in sunscreen and wearing towels on their heads are deep in rehearsals of "Washington Square Moves," Matthew Witten's play in the amphitheater.

Though Matt Witten has a TV movie under option, he is here to develop a play about a homeless character in Washington Square who is also a brilliant chess player. "My first draft was very lean and spare," he says. "I knew a lot more about the characters than I put down on paper. But my director and dramaturg told me I could tell the audience more. So the writing I've done here is mostly working at putting on paper what was in my mind. The characters are deepened, fuller and richer than they were. The plot and structure and style is the same."

While Witten added material, he also cut. "The actors show me the cuts it needs. That's what I'm doing now." In the middle of it, he was happy with the process. "If I could have a play started anywhere, it would be here."

Rick Cleveland was about to go into rehearsals with "Homegrown," about an Ohio farm family that gets involved with a pot grower. (Despite the Cleveland and Ohio connection, Rick is from Chicago.) "I wasn't sure what I had when I got here," he said. "When I read it out loud I began to see new possibilities. I was aware that the story and the characters needed to be fleshed out. This experience is overwhelming-- the caliber of people paying attention to your work."

P.J. Barry is a successful New York actor with television and commercial parts paying the bills, and grants to help support his extensive playwriting. His play is a comedy about a small town criminal's dying attempt to guarantee his daughter's happiness.

"My play's in pretty good shape. I'm waiting to get it to the actors on Friday. I've been talking to my dramaturg, Max Wilk, but my director has been working on other shows so we didn't talk much this week. I fixed the problem we identified. But right now I'm getting a little antsy. I want to get rolling." Barry had also dealt with some questions about his script by how he read it at the playwrights' reading. "Being an actor, I'm comfortable reading it. And they could hear what I mean."

Paul Zimmerman was looking forward to his first rehearsal on Monday as well. "So far I haven't made huge changes. I'm very anxious to hear the actors now. This is supposed to be a funny, angry play. It's about the paranoid author of children's books, a series called 'Cream Puff, the Friendly Cloud.' The rhythms are very important, so I want to work on the music of the piece. My director is Walter Dallas, and I feel very much on the same page with him. August [Wilson] is my dramaturg, and he's been very helpful. "

Paul had been a little concerned about the O'Neill lifestyle at first. "Summer camp made me miserable," he said. "But I got past that. I eased into this, and now it's really great to be here. This is at the top of what I could have hoped for."

Jeff Hatcher's play would be going into rehearsal on Thursday. Among the playwrights, he was one of the more experienced. "It's a 65 or 70 minute one act about vandalism at an art gallery, a locked room mystery, written as a high Tory cartoon," he said " I don't do major rewriting until I hear the actors begin to speak. Actors will get at the questions faster than the writer. The four day rehearsal period is tricky, though. Like Paul's play, mine needs to be done with a cracked naturalism. It's hard."

Although he loves returning to the O'Neill, he doesn't disapprove of the new O'Neill policy that no longer gives special priority to script submissions by past participants. "It's a level playing field. Every year there are one or two writers that come out of nowhere. The writers are especially young this year."

One of the writers more or less out of nowhere---that is, California, where he writes computer manuals for a living---is John Darago. Perhaps because he has the least theatrical experience, his play is scheduled to be last, giving him the most time to work on it. "This is the first play I've written in fifteen years," he says. "And this is the first one that's ever gotten this close to production. The structure of it was sound from the beginning, but I needed to work on character. My dramaturg is Corrine Jacker, and she has made all the difference. She really knows how to get me to work, and what I need to be doing. I'm going to have a much stronger play as a result. I don't think I ever could have done it without all this help. This process has met and exceeded my expectations."

With his production and critique of his teleplay "A God in the House" occurring on this day, Peter Selgin was at the exact center of the process. "I think this piece came a long way. I set high goals and I think we met them, but there's still work to be done-we did a lot but we only did it in a week. I want to see how much further I can take it. I believe in building something to last. We found the structure, and that's most important. I think I'm gong to bring back things I changed---on reflection I changed things I shouldn't have. We pulled some punches."

Sometimes writers worry about making changes they'll regret later, Lloyd Richards had mentioned, so now at the beginning of the conference he shows them a sealed envelope containing their play as it was when they arrived, so they know that they still have it no matter how much they change it later.

There were still two weeks left, but nearing the end of his most active phase, Selgin was already starting to feel elegiac. "I'll apply next year, and I'm sure it will be emotionally harder to deal with not getting in. Now that I've been here I feel these people are my friends. I'm curious now about other places that develop plays, but this place...being by the water makes it very special. And other places are not as haunted by people you know have been here. You feel you're part of a tradition here."

Meanwhile Charles Schulman, emerging from an all-night rewrite to fix a major problem on his play ("Angel of Death") that had emerged in his first rehearsals at the Instant Theater, was also feeling a tinge of gloominess about the summer's end. "What's so overwhelming about this process," he said, sprawling on a couch in the Mansion living room, "is that it's the exact opposite of being ignored. Too bad it's only a month. Too bad there's not some middle ground between being here and real life, where you are always ignored."

Rick Cleveland agreed. "I've been working in professional theatre for about 10 years now, and especially lately I've felt extremely burned out. I can't tell you how many times I've thought about quitting and going back and getting my degree in some totally unrelated area. But surrounded by these people paying this much attention to my play, it's a total cure for burnout. I feel like I want to be a playwright forever."

"That's what this place is about," Jeff Hatcher commented. "Great environment, good actors, good directors, people dedicated to your own work, which is something you don't find in most of the American theatre---very few places are you going to find writers having the power to do the things we have the power and responsibility to do here."

|

| George White and Lloyd Richards in 1991. Smiths. Mag. photo |

After two more weeks of plays, critiques, beach time and a crushing heat wave, the 1991 conference ends, but the Center's work continues. Under George White's continuing leadership and with a loyal staff, the Eugene O'Neill Center is a nonprofit institution with year-round activities: the National Theater Institute for college students during the school year, and summer programs in puppetry, musical theater and cabaret. The National Drama Critics Association fellows program runs concurrent with the playwright's conference. The O'Neill also sponsors related activities ranging from arts programs for Connecticut school children to the American-Soviet Theater Initiative. "Fortunately, it's still evolving," George White says.

While White manages the O'Neill's external affairs, Lloyd Richards presides as the Zen Master of the playwright conference's internal workings. "My responsibility essentially is to create an environment where chances can be taken, where failure is not a stigma, but a step towards growth," he said. Richards recently retired as dean of Yale Drama School after 12 years, but intends to stay with the O'Neill. His commitment is perhaps suggested by the last play he directed at Yale: "Moon for the Misbegotten."

The O'Neill process has become an international model for developing new plays and playwrights, spread in part by the O'Neill itself or its alums: Frank Gagliano is artistic director of the Showcase of New Plays at Carnegie Mellon University; Jeff Hatcher of Minnesota's Midwest Playlabs. But the funding cuts that vanished a quarter of the conference budget also gave this summer a subtle smell of threat.

"There's been more of a garrison mentality this year because of that," said Phil Bosakowski, who also attended in 1990. "We feel more closely knit. Last year I was happy to be here. This year I'm relieved to be here."

"I hope places like this don't disappear," said Charles Schulman. "This is a possibility and it would be tragic, because writers don't have any status anywhere else."

"If the O'Neill isn't around, I don't know what's going to happen," said John Seitz. "Before there was any other concerted dedication to the voices of American theatre, the O'Neill was there."

Many of the participants were hoping to be back in 1992, including August Wilson-but this time as a playwright again. Meeting the O'Neill deadline has become part of his inspiration.

"I generally start in October or November," he said, sipping coffee on the Blue Genes patio. "I have this ritual of finishing the play on December first, going to the coffee shop and making copies, and making it to the mailbox at like eleven thirty, buying these one dollar Eugene O'Neill stamps and pasting them all over the envelope, and dropping it in the mailbox."

Postscript

August Wilson brought two more plays to the National Playwrights Conference: Seven Guitars

in 1994 and Gem of the Ocean

in 2002.

With Radio Golf

in 2005, he completed his monumental ten play cycle, each one set in a different decade of the twentieth century. He was triumphant when he finished it, and talked about plays he was now free to write, including a comedy. But that June he was diagnosed with liver cancer. He died in October.

All ten of these plays were produced in New York, and eight of them won the New York Drama Critics Circle award for best play or best American play of the year. Several theatres outside New York have since produced all ten, including the Public Theatre in Pittsburgh. Of all the American playwrights named in this piece, his work has proven the most enduring.

August Wilson and I were nearly the same age, and we grew up some thirty miles apart, with some cultural totems in common, like the Pittsburgh Pirates. I could spot specific Pittsburgh characteristics in him. We fell into an easy rapport--in my notes I commented that at the dinner table one evening we were refilling each other's coffee cups. August had a great sense of humor, even about himself. He said that conference attendees referred to his four hour version of what became Fences as A Long Day's Journey into Morning.

I saw him a few times after that summer, always in Pittsburgh, once when he was in town working on the premiere of a new version of his very first play, now part of his 20th century cycle, called Jitney. I saw that performance at the Pittsburgh Public Theatre (with some props from the actual places in the play) and spoke with him afterwards. I saw performances of several of his plays at the Pittsburgh Public over the years. It was always special to see a Pittsburgh centered play in Pittsburgh.

It was perhaps five years after this conference that I saw him again, just after he'd received an award during an academic conference at the University of Pittsburgh's Cathedral of Learning, across the street from where the Pirates played at Forbes Field in our childhood. As happened with others I met that summer of 1991 and ran into or corresponded with later, the bond established then was simply revived for a moment. For one thing, he told me with some pride that he'd quit smoking. (It turned out to be one of several aborted attempts.) That was the last time I saw him.

Lloyd Richards retired as the O'Neill artistic director in 1999. All together he directed five of Wilson's ten plays, and won awards for four of them. He died on his 87th birthday, June 29, 2006, two days before the National Playwrights Conference usually began, and one day before my own birthday. Noting his death I wrote this postscript to that 1991 conference: "He was utterly respected by everyone, for his discipline and gentleness, his rigor and humor, his attentiveness to detail and insistence on communicating the big picture, so that everyone knew and shared the same vision of the O'Neill process."

|

| George C. White photo by A. Vincent Scarano |

Founder George C. White retired from running the O'Neill in 2001 after 37 years at the helm. He was honored with a benefit performance in New York, with guests including actors Michael Douglas and Charles Dutton, Lloyd Richards and O'Neill playwrights John Guare and Jeffrey Hatcher.

White was inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame in 2013, and the O'Neill Center gave him their 2022 Monte Christo Award for extraordinary contributions to American theatre. It was to be presented by Michael Douglas, but at age 86, White was too ill to attend in person. While running the O'Neill, White had directed plays in a number of American theatres, as well as directing "Anna Christie" by Eugene O'Neill in Beijing. White was also the founding chairman of the Sundance Institute.

|

| portrait of Edith Oliver by Scott Gordley |

Edith Oliver ended her distinguished tenure at the New Yorker in 1993. She'd started in 1947. She spent twenty summers at the O'Neill, from 1975 to 1995. She died in 1998, and in that year the outdoor Instant Theatre at the O'Neill was renamed The Edith in her honor. She was known for a caustic wit but was lauded for championing new voices in New York theatre.

|

| Tom Szentgyorgyi |

Many of the playwrights of summer 1991 continued writing for theatre, some for film, and several became especially successful in television.

Tom Szentgyorgyi, the playwright I followed most closely for the piece, continued writing plays ("Among the Thugs," adapted from a book by Buford, played at Chicago's Goodman Theatre in 2001) but made his name as a writer and producer in television. He worked with Aaron Sorkin (as a writer on "Sports Night") as well as Steven Bochco (on "NYPD Blue" and especially as writer and producer on the series, "Philly.") Among the series he later executive produced were "The Mentalist" and "Bull." One of the writers he employed on "The Mentalist" was another 1991 O'Neill playwright, Jeffrey Hatcher.

Charlie Schulman's O'Neill play, "Angel of Death" was later produced by the American Jewish Theatre. He's had other plays produced at Circle Rep and Playwright's Horizon in Manhattan, wrote for TV and film, and wrote a sketch comedy that ran for three years at the Apollo Theater, which he later scripted as a movie. He returned to the O'Neill in 1998.

Peter Selgin's 1991 O'Neill play, "A God in the House" was optioned for Off-Broadway. He has since published novels, a short story collection, non-fiction and travel books, in addition to winning several playwriting competitions, and making a name as a visual artist. He teaches at Georgia College and State University.

Paul Zimmerman's 1991 play was produced as "Pigs and Bugs" at the Echo Theatre Company in Los Angeles and elsewhere. He wrote the screenplay for "Love, Brooklyn" selected by the Sundance Film Festival and "Modern Affair," and served as the screenwriter-in-residence for Tribe Pictures. He wrote more for the stage, and teaches at Hofstra University.

Rick Cleveland's 1991 O'Neill play, "Home Grown," was later produced at the Ventura Court Theatre in Hollywood. He returned to the O'Neill in 1993. He won a writing Emmy for a 1999 episode of "The West Wing" along with Aaron Sorkin. He became a TV producer for the "Six Feet Under" series, and other series such as "Mad Men," "House of Cards" and "The Man in the High Castle." He also wrote the 1998 indie film "Jerry and Tom" (with Joe Mantegna and William H. Macy), adapted from his play presented at the American Theatre Company.

Matthew Witten, later writing under the name of Matt Witten, is probably best known as a chief writer for the megahit series, "Law and Order." That New York-based series has featured several actors I met at the O'Neill (including John Seitz, playing--as he predicted--a cop), as well as actor/playwright P.J. Barry. He wrote for and produced a number of other television series, and is the author of a series of Jacob Burns mystery novels.

Jeffrey Hatcher's professional playwrighting career has stretched from "Scotland Road" in 1993 to (so far) "Holmes/Poirot" in 2024. He's probably best known for his stage adaptation of "Tuesdays with Morrie," which he developed at the O'Neill in 2001. His plays are produced all over the U.S. and probably beyond. Among his movie credits is the 2015 "Mr. Holmes" starring Ian McKellan, and he's written extensively for television.

Patricia Cobey returned to the O'Neill the very next year, in 1992. She had scripts produced by BBC radio, and was writer in residence at Washington University. Gannon Kenney wrote the first episode of the 1998 series "Seven Days" an episode of "Star Trek: Voyager," and original scripts for television.

P.J. Barry, who'd already had a play on Broadway ("Octette Bridge"), continued writing for the theatre as well as acting in television and film. Several of his plays were produced at the Hudson Guild Theatre in New York, where he was artistic director. He was also director of the Fulton Theatre Company. Barry died in 2019 at the age of 88.

|

| Phil Bosakowski photo by A. Vincent Scarano |

Perhaps the most poignant postscript is for Phil Bosakowski. He became resident playwright at Princeton in 1992, and returned to the O'Neill as dramaturg in 1993, where he got married in a ceremony on the O'Neill grounds that summer. But less than a year later he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and he died in 1994 at the age of 48. There is now a Phil Bosakowski Theatre dedicated to him at Primary Stages in New York.

I had a great time at the O'Neill that summer, and all the playwrights were friendly and collegial. But it was Phil Bosakowski who surprised me as we began one interview just before I left, by commenting that my presence had been a positive addition to the conference that year---not just the fact that I was writing about it, but me personally. I was very flattered and very grateful to hear him say that.

|

| John Seitz with Christopher Plummer in "No Man's Land" |

Finally, the most fervent of the actors I interviewed in 1991 was John Seitz. He had a long career primarily Off-Broadway. He had a memorable role in the 1994 revival of Harold Pinter's "No Man's Land," which starred Jason Robards and Christopher Plummer. He won his second Obie in 2001 for a Public Theatre production. But his greatest dedication was to the National Playwrights Conference at the O'Neill. Over 20 years, he worked in more than 100 new plays. He died in 2005 at the age of 67, having asked that his ashes be spread at the O'Neill.

.jpg)